On a sunny day, the placement of the Elmira Correctional Facility seems inappropriate for a maximum security prison. If you make it to the top of several very steep flights of stairs, you’re rewarded with several views; the first being the town of Elmira and the picturesque Finger Lakes region, brilliant in its fall foliage.

The second is a crudely constructed sculpture of two naked men.

“I’m thinking, ‘Oh boy, the jail with the two naked guys out front,” Elmira Correctional Facility Superintendent Paul Chappius says with a sigh. That was his first reaction when he found out he would be transferred to Elmira from Attica, a notoriously rough prison in New York.

This morning we’re visiting Chappius, who began his tenure as Elmira Correctional Facility’s top dog only a month ago. He’s so new that his name is vacant from the signage on the grounds outside.

Mark Twain, actually, is the reason we’re at the Elmira prison in the first place. He tried out a few of his lectures on the inmates before the building was a maximum security prison.

Chappius quips that it must have been a “captive audience.”

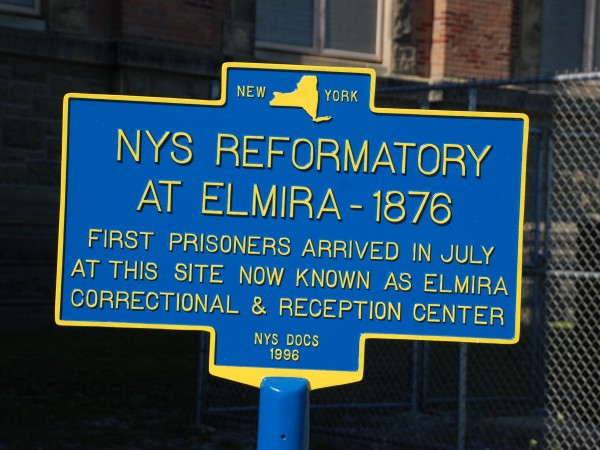

Although Chappius is new, the prison has quite a history. The facility, which was originally a mere reformatory, opened in 1876. In older pictures it looks like a castle or a mansion. But in 2003 two inmates managed to get onto the roof, tie bed linens together, climb down and escape. The media snapped an embarrassing photo of the prison, sheets still hanging from the roof. After that barbed wire and razor ribbon went up everywhere. The outside of the building looks more prison-like these days, spiky and imposing.

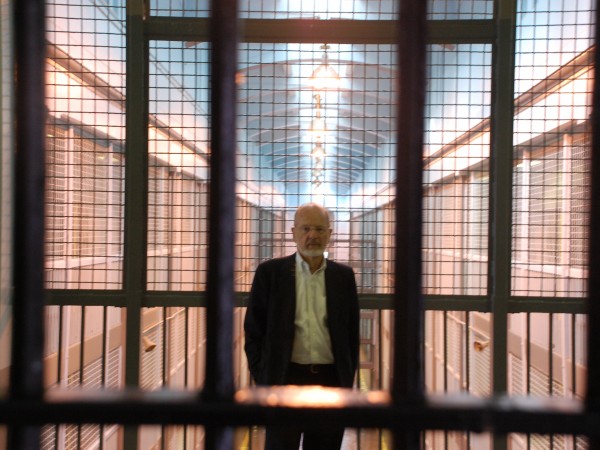

The inside, however, is more inviting than we expected. The history of the place and its thick layers of paint make it accidentally charming when you’re on the right side of the prison bars. The guards are chummy with one another but they also interact with the inmates in positive ways, leading to what leadership calls “relaxed control” and a clean, organized facility.

Chappius welcomes us into his office, which is filled with New York Yankees’ paraphernalia. The Yankees are big around here, and their emblem is painted on walls, doors and floors. Chappius is a friendly man with sandy hair and a matching mustache, but we don’t want to push his good will by bringing up the Yankees’ recent loss.

He calls Stephen J. Wenderlich, deputy superintendent of security, to join us and fill in some of the details. Chappius has been here a month, Wenderlich, 12 years. He strides over from his office, and a momentary air of formality descends upon the room.

Wenderlich looks official in a head-to-toe gray uniform. He uses a perpetual “yes, sir” or “no, sir” and dutifully supports all of the superintendent’s statements. Soon enough, though, a sly smile breaks through Wenderlich’s boyish face. Dan, Loren and I aren’t sure how to react when he eventually starts making jokes.

Wenderlich is “the numbers guy,” Chappius says. Wenderlich explains that Elmira holds approximately 1,800 inmates, which include prisoners in the maximum security facility and the reception center. Security staff here is about 600.

“The facility is like a city,” Wenderlich says. “Everything you find in the city of Elmira, you find in the correctional facility of Elmira. There’s doctors, electricians, plumbers.”

The biggest issue the correctional facility tries to address—in a change from recent years—is the mental health of the prisoners.

“You can imagine, prison is a tough environment anyway,” Wenderlich says. “(Prisoners) come with their backgrounds, and then you put them all together and say, ‘Now get along.’”

Wenderlich and Chappius remember when a prisoner’s mental health status was no consideration at all.

“Old-school prison,” as Wenderlich calls it. “It was just ‘Keep ‘em in, don’t let ‘em out.’”

These days a prisoner’s mental health is evaluated before almost anything can happen, be it disciplinary action or housing placement.

“Ten years ago, if you told an inmate to do something and he didn’t do something, you took action, and it was usually physical,” Wenderlich says.

Of course staff members still grapple with stereotypical issues of running a prison, specifically drugs and gangs. Just the other day, Chappius says, a mother and sister smuggled in 23 grams of marijuana. Even a grandmother was caught once.

Gangs, and criminal organizations in prisons, are a correctional officer’s worst nightmare, Chappius says.

“We know there are gangs,” he says. “We know they are there but we do not acknowledge them. We do not empower them.” He vaguely alludes to the policies of other states, in which officials negotiate with prison gang leaders, and expresses his distaste.

On the other hand, Wenderlich eagerly expresses approval for Chappius’ policies in place in Elmira.

Chappius’ first motto—”Helplessness and hopelessness are detrimental”—is connected to his second,“walking and talking.” Walking and talking is very straightforward. It means guards get on the floor with the inmates and engage in human interaction.

“My wife says, ‘Well, you don’t go back there, do ya?’” Wenderlich says, affecting a tone to mimic his wife’s worry. “I say, ‘Oh yeah, honey, I do,” he says excitedly. Even the higher-ups are expected to interact with inmates in the prison setting.

Before our guided tour, Chappius says most people expect to see inmates in their cells, or officers standing over inmates.

“You’re going to see a clean, organized facility,” Wenderlich told us. “You won’t feel the tension in the air. It’s kind of a relaxed control.”

The two escort us past the security checkpoint outside of their sterile offices and into the prison, and we prepare to see this “relaxed control” that they had been talking about.

There’s a board filled with green and red metal tags hanging on pegs. Wenderlich and Chappius flip their tags over. In case of emergency, staff needs to know who’s in and who’s out, who’s green and who’s red. The action has an ominous feeling about it, reminding us that the situation can change as easily as they flip the tags over.

We enter the E Block, which can hold 148 prisoners when it’s full. The walls and bars are white and sky blue, with cerulean accents. The way the light filters in from the window and the cells stretch up to the ceiling, it’s sort of like being underwater.

Almost immediately Chappius sees a sheet tied to the bars across an inmate’s cell, blocking the inside from view. He strides over and forcefully knocks it down. He gives the prisoner a sharp verbal reprimand. It’s a little scary.

Chappius never intended to get into the prison business. In fact, he downright wanted to avoid it. He meant to be a dairy farmer with his father.

His mother was a switchboard operator at the local prison. “I had told her there was no way I would ever be a damn prison guard,” Chappius says.

On the sly, she forged his signature and signed Chappius up to take the prison guard test. You can imagine his surprise when he received something in the mail. He still wasn’t going to take the test. But the night before, “everything that could possibly go wrong on a dairy farm went wrong on a dairy farm.”

He got up the next morning and took the test. He scored a 98.

Loren asks Chappius when he changed his mind.

“When I was standing knee deep in cow manure,” he says.

We pass through the historic D Block, which was built in 1876. There are several levels of cells, and they face one another across a large open space.

In the B Block, Chappius pauses in front of another cell. “You all right?” he asks its inmate softly.

“A little cold,” the inmate replies. Chappius expresses his sincere concern.

It’s cold in the prison, despite the Indian summer weather. But once the heat’s on, it’s on. With 80-degree weather coming this weekend, the prisoners would roast, he says.

All throughout our prison tour, we see evidence of the “walking and talking” Chappius described. He and Wenderlich address prisoners by name, ask them how they are doing and tell them they’ll try to get them home.

We pass rows and rows of cells. Inmates sit on their beds and read or write. Some have TVs.

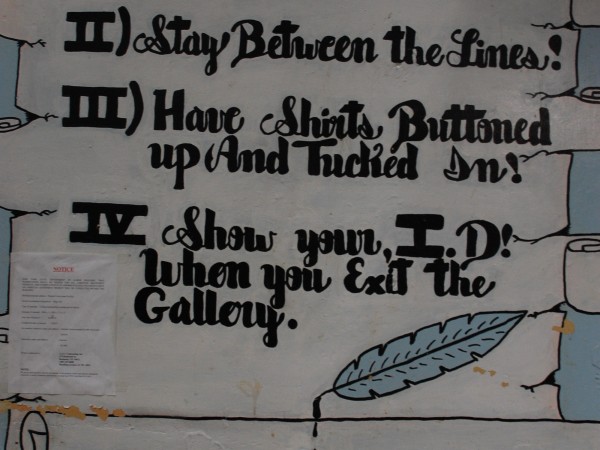

“Each block has its own personality,” Chappius says. “They take a lot of pride in what they do and how it looks.” Some of the prisoners’ paintings on the walls are quite elaborate. Aside from the pervasive Yankees logo, there are also nature and nautical scenes.

Our only rule today is that we can’t take photos of inmates, and this leads to entire blocks being cleared out once or twice on our behalf.

Wenderlich takes us inside a momentarily vacant cell in the historic D Block. Wenderlich is eager to point out photo opportunities. He’s a very enthusiastic man (also evidenced by the numerous comments he has left on our website, asking us if we enjoyed the tour).

The cell is so small that photographing the space is a challenge. There’s a tiny sink and a toilet. Green sweats are hanging on a clothes line against the side of the cell. A Rolling Stone cover is taped to the wall, along with a few glossy pages from a men’s magazine featuring women blowing kisses. Those are the pictures you can see from the outside. The really raunchy, eye-poppingly pornographic photos have to be on the opposite wall, which isn’t visible from the corridor. There are considerably more of these.

In a large, open room there’s a group of Rastafarians, many with long dreadlocks, sitting at tables and standing around, talking. They’re holding a special religious event.

“They get to do what Rastafarians do,” Chappius says. “Except smoke,” he laughs.

We pass through the mess hall, and the silver tables and benches are gleaming. A glass office overlooks the large room. Just as we’re getting a bit too comfortable, Chappius subtly reminds us where we are. He tells us officers can deploy different doses of “chemical agent” if necessary. “Also known as tear gas,” he adds.

The scullery behind the mess hall is bustling with activity. Inmates wash dishes and do other tasks. (“They’re going about their jobs,” Wenderlich says. “Just like you’d see in a college cafeteria kitchen.”)

Outside of the prison, there’s a recycling center, which sits in front of six units used for conjugal visits. Nearby, it looks like the Main Street of a city. Rows of brick buildings used for inmate classes face one another.

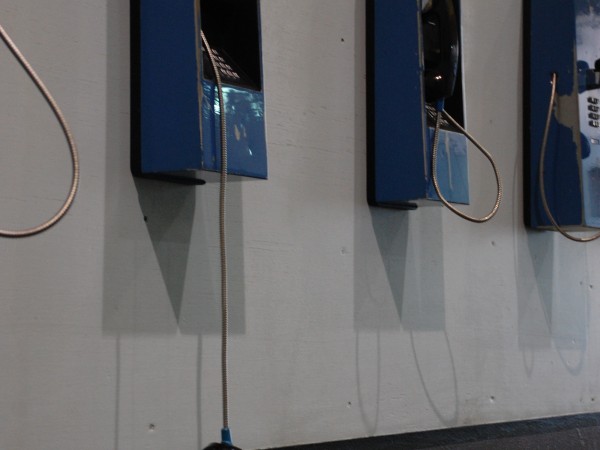

The Fieldhouse is the main attraction. It’s used for recreation. Inmates get a minimum of one hour of recreation a day, but most get many more. When we arrive, it’s eerily empty. There are basketball courts, phones and four TVs. There’s something for everyone: one TV is used for sports, one is used for movies, another runs BET and the last is for a Hispanic channel, Wenderlich says.

Once again, Chappius draws our attention to the glass office above the basketball court. “The officer up there has a gas gun,” he says. “And, yes, we have dropped chemical agents in the past,” he says, anticipating our next question.

As we walked outside through a courtyard, a few inmates yell out of their windows at us. It’s the rowdiest behavior we see.

Chappius, who has been more than generous with his time, runs off to a meeting. Wenderlich leads us out through an impressive, terrifying maze of barbed wire and razor ribbon. He points out one last photo opportunity before we go.

Alyssa

Pingback: Twain and the Elmira Correctional Facility – Traveling with Twain

Karas missed the trees. She should look at the damage this prison inflicted on Elmira. What happens when cons and their families settle into a nearby community? Well, that town dies. Why is Elmira so lacking in industrial and commercial development? Why does the town look like the aftermath of a WW II bombing raid?